Field Trip: Cornwall, part 2

January 15th, 2014 | Posted in: Field Trips, Images, Travel

After the rising tide halted my zawn hunting at Land’s End I drove along the south coast to the little village of Treen to photograph the Logan Rock. Logans are boulders that wobble (but they don’t fall down) they are formed when horizontal faults in stone outcrops are eroded to leave just one or two points of contact between separate masses. Sometimes huge rocks are balanced so finely that the slightest nudge can set them moving. This was once the case with the Treen Logan, an 80 ton block of granite perched on a cliff just south of the village, which according to historical reports “move[d] obsequious to the gentlest touch”. In the 18th and 19th Century tourists visited the village in their thousands to see this marvel and were hoisted and hitched up the steep cliffs by local guides to try their hand at shifting it’s epic weight.

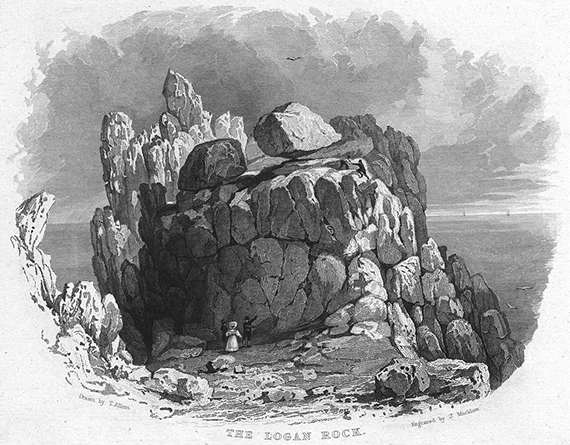

This engraving from around 1830 takes a little artistic license with the precariousness of the perch but the scale looks pretty accurate to me. I think the gesticulating man at the bottom is trying to convince the lady that he can get her up there, bonnet and all. By the time this engraving was made, though perhaps some time after the original sketch, the logan’s legendary invulnerability to toppling had been put to the test with dramatic results. In April 1824 a group of sailors from HMS Nimble, bored and frustrated by their appointed task of fixing marker buoys to dangerous offshore rocks, unleashed their energies on the logan with iron bars and ropes and managed to unseat it. I imagine there was a moment of triumphant release, cheering and back-slapping, before someone realised that they were all now in deep trouble. Perhaps the awful realisation came the next morning, once the joy and the rum wore off, like the plot of a 1800’s The Hangover.

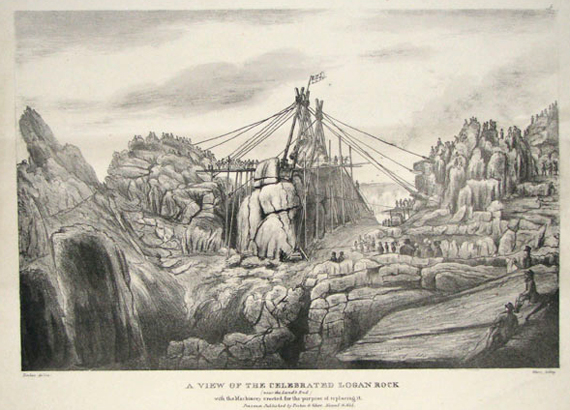

Condemnation of the act came hard and fast and the Admiralty was drawn into the storm. The leader of the group, Lieutenant Hugh Goldsmith, was commanded to put the rock back at his own expense, though he was given materials and equipment from navy stores to accomplish the task. Predictably, putting the rock back was a greater test of Goldsmith’s ingenuity than knocking it over and took several months. The task was completed by sixty men with block and tackle and scaffold in November 1824 at a cost of £130, probably enough to put a severe, if not terminal, hole in the young Lietenant’s finances.

Although it was back in it’s seat, the rock was no longer quite so obsequious to the touch as it once was, and perhaps because of this tourism to the village dwindled. Goldsmith was never forgiven for his act of vandalism and was blamed for Treen’s fading fortunes, although it’s quite possible that the public’s tastes were just becoming more sophisticated, and moving rocks, even massive, moving rocks, no longer held the same attraction. There was a crowd of over a thousand when they put the rock back, if only they could have knocked it off and put it back every week, now that’s entertainment.

The rock does still rock, just about. I tried it myself and it’s not easy but it is possible to get it gently moving if you lift at the SW or NE (I think) corners. The image at the top is not the Treen Logan by the way, it’s another logan on Bodmin Moor. There are several logans in Cornwall and Devon, the structure and erosion of granite is particularly conducive to their formation. I’d love to hear of others in different geological contexts so please leave an comment with details if you know of any.

In part 3: Gloups