Tolmens, dolmens and lumbago

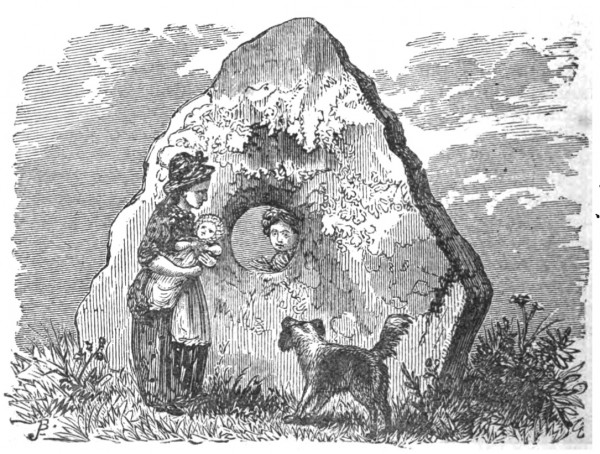

February 3rd, 2014 | Posted in: Field Trips, Religion, Science, Video, Word stuffTolmens are stones that are both objectively holey and subjectively holy. When they were found by prehistoric peoples in what is now Devon and Cornwall, the neat circular holes in these river stones would have been impossible to explain, and this imbued the tolmens with mystery and the possibility of magic. Healing rituals involving these stones persisted into modern times, often having been co-opted by Christians from pre-existing pagan rites.

Here’s an account from William Bottrell’s Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall published in 1873:

IN a croft belonging to Lanyon farm, and about half a mile north of the town-place, there is a remarkable group of three stones, the centre one of which is called by antiquaries the Men-an-tol (holed stone), and by country folk the Crick-stone, from an old custom—not yet extinct—of “crameing” (crawling on all fours) nine times through the hole in the centre stone, going against the sun’s course, for the cure of lumbago, scatica, and other “cricks” and pains in the back. Young children were also put through to ensure them healthy growth.

The holes in the stones seem to have presented two particular uses: firstly as a portal for passage to another place or state of being, for example a state of being where you didn’t have back pain; and secondly as an aperture for sunlight. Some of the holes can be quite small and would have presented a challenge as significant as any yogic exercise to potential patients; the necessary stretching and contortion might explain any perceived benefits afterwards. It’s also worth noting that the smaller holes would have been only passable for the very svelte and that tolmen treatment was probably the first medical intervention to have been denied on the basis of obesity.

The mystery surrounding the origin of tolmens and similar features, like rock-cut basins, was solved when scientists studying fluid dynamics observed tornado-like currents developing when fast flowing water meets large obstacles. These currents, called kolks, multiply forces into a water twister that can lift and carry huge blocks. On a small scale, rocks held in a kolk can pound and gouge out circular basins in the riverbed, or on overhanging ledges, where the eventual result is a hole right through the stone, thus creating a tolmen.

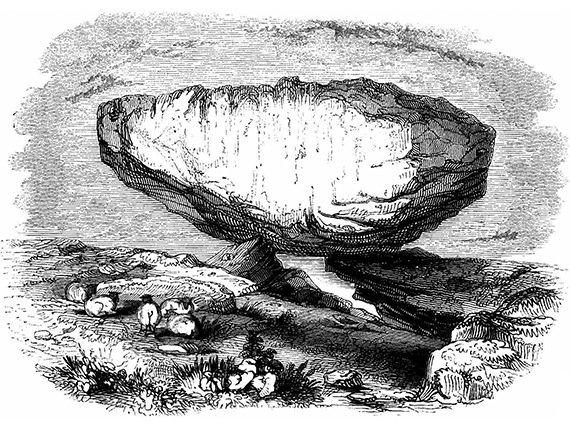

Looking into the historical records of tolmens, I came across a bit of confusion with the word dolmen. 18th Century historian William Borlase’s book Observations on the Antiquities Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall, published in 1754, features a fine etching of the tolmen at Constantine in Cornwall (above). This massive stone was riddled with holes (rock basins) on its upper surface, hence the name tolmen, but it also rested on the points of the stones beneath so resembling a megalithic tomb structure called a cromlech. Borlase’s work was widely read especially among the growing numbers of “Celtomaniacs” in Britain and France who lapped up his fevered speculations on the rites of Celtic druids.

One such Celtophile was the French officer and antiquarian Théophile Corret de la Tour d’Auvergne who published in 1796 a work entitled Origines gauloises (Celtic Origins) in which he says of megalithic tombs: “The enormous stone that covers this monument from antiquity is known in our language as a dolmin.” This is the first recorded use of that word and Corret de la Tour d’Auvergne’s assertion that it originates from Breton has apparently no factual support, so it seems possible that he appropriated the word (wrongly) from Borlase’s work, which was almost certainly know to him. Attempting to pronounce “cromlech” with a thick French accent should give a useful insight into the reasons why the word “dolmen” quickly caught on and in fact came to refer to the whole tomb structure and not just the upper stone. In the early 19th Century, the word “dolmen” with it’s new meaning came back to Britain having been adopted by the newly developing science of archaeology and the rest is history.

Théophile Corret de la Tour d’Auvergne (pictured above as both soldier and scholar) also introduced the word menhir into use (who knows what Obelix would have delivered without him, tolmens possibly). After his death Théophile’s heart was apparently owned by Garibaldi (his actual heart, that’s not a necro-romantic metaphor).